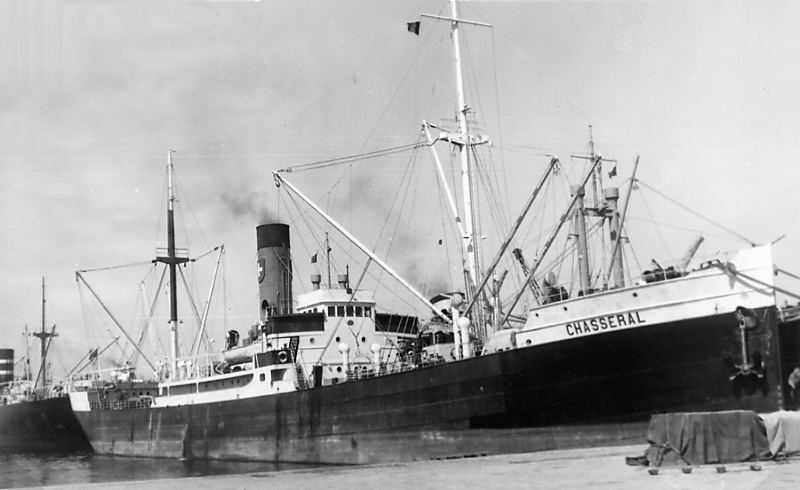

CHASSERAL

Schiffstyp / Ship's type: Dampf / Stückgutfrachter / Steam General Cargo Vessel

![]()

Bau / Construction

| Bauwerft / Shipyard: | Hall, Russell & Co. Aberdeen | ||

| Bau Nr. / Hull / Yard No.: | 303 | Baujahr / Year of built: | 1897 |

| Kiellegung / Keel laying: | n.a. | Stapellauf / Launching: | 20.08.1897 |

| Ablieferung / Delivery: | 00.10.1897 | ||

![]()

Reeder - Manager / Shipping company - Manager

| Eigner / Registered owner: | 03.07.1941 Eidgenössisches Kriegs-Transport-Amt (KTA) (WTO), Bern / 11.03.47 Nautilus AG Glarus | ||

| Reeder / Shipping Company (Manager): | 03.07.1941 Honegger & Ascott, London / 11.03.47 Nautilus S.A., Lugano | ||

| Tech. Management / Technical Mgmt.: | 03.07.1941 Honegger & Ascott, London / 11.03.47 Nautilus S.A., Lugano | ||

| Management von / from: | 03.07.1941 | Management bis / until: | 11.03.1947 (KTA) 08.10.1951 (Nautilus) |

| Registerhafen / Homeport: | Basel | Flagge / Flag: | Schweiz (CH) / Switzerland (CHE) |

| Rufzeichen / Call sign: | HBFD | CH-Register-Nr. / Official No.: | 6 |

| - | - | Klassifikation / Class: | LR (Lloyd's Register) London |

| Registrier Datum / Date: | 10.07.1941 | Register Streichung / Deletion: | 08.10.1951 |

| Verbleib / Fate: | Verkauf nach Italien / Sold to Italy | ||

![]()

Vermessung / Tonnage

| BRT / GRT: | 3'128 | Länge / Length: | 100.60 | Meter | ||

| NRT / NRT: | 1'874 | Breite / Breadth: | 12.55 | Meter | Fahrgäste / Passenger: | 12 |

| DWT: | 4'064 | Tiefgang / Draft: | 5.64 | Meter | Besatzung / Crew: | 31 |

| Lightship tons: | n.a. | Tiefe / Depth: | n.a. | Meter | Airdraft: | n.a. |

| Ladewinden / | Cargo winches: 8 | |||||

| Ladegeschirr / Cargo gear: | 8 Ladebäume / 8 Derricks n.a. ton-SWL (Safe Working Load) | |||||

![]()

Maschine / Machinery

| Maschinen-Typ / Engine type: | Triple expansion reciprocating steam engine (T-3-cyl.) |

| Maschinenhersteller / Engine builder: | Hall, Russell & Co. Aberdeen |

| Leistung / Power: | 1'874 PS / HP |

| Geschwindigkeit / Speed: | 12 Knoten / Knots |

| Antrieb / Propulsion: | 1 Festpropeller / Fixed blade propeller |

![]()

Registrierte Schiffsnamen / Registered ship's names

| Datum / Date | Schiffsname / Name | Heimathafen / Homeport |

| 00.10.1897 | Ingeli | Aberdeen |

| 00.10.1911 | Ingeli | Liverpool |

| 00.00.1913 | Tegucigalpa | La Ceiba |

| 03.07.1941 | CHASSERAL | Basel |

| 08.10.1951 | Mar Corrusco | Genova |

| Verbleib des Schiffes / Fate of vessel: | 1953 verschrottet / Broken up |

![]()

Schiffsgeschichte

Am 20.08.1897 vom Stapel gelaufen und im Oktober 1897 wurde der Frachtdampfer INGELI auf der schottischen Werft Hall, Russel & Co., Aberdeen, fertiggestellt (Baunummer 303) und der Eignergesellschaft John T. Rennie and Son, Aberdeen, übergeben (offizielle Nr.: 108651, Rufzeichen: PVJD). Das Schiff wurde von einer Dreifach-Expansionsdampfmaschine der Firma Hall, Russel & Co., Aberdeen, angetrieben (1’810 PS) und erreichte eine für die damalige Zeit beachtliche Reisegeschwindigkeit von 12 Knoten. Es bot zudem 36 Passagieren Platz. Ursprünglich war das Schiff am Vormast noch mit Rahen für eine Hilfsbesegelung ausgerüstet. Das Ladegeschirr bestand aus 3 Ladebäumen. Das Wort INGELI stammt aus der Zulusprache und bedeutet Kälte, Schnee oder Graupel, ist aber auch der Name eines Berges in KwaZulu-Natal. 1911 wurde der Dampfer an die Charente Steamship Co. Ltd. in Liverpool verkauft, welche ihn der Reederei Thos. & Jas. Harrison, Liverpool ins Management gab. 1913 erfolgte ein Verkauf an die honduranische Firma Vaccaro Brothers Ltda., La Ceiba. Sie gab dem Schiff den Namen TEGUCIGALPA. Mit der Registrierung unter der Honduras Flagge erhielt es das Rufzeichen: HRBB. Im April 1920 wird die Tegucigalpa Steamship Corporation neue Eigentümerin, während die bisherige Eignerin, die Vaccaro Brothers Ltda. das Management übernahm. Gleichzeitig wird das Schiff von Kohle- auf Ölfeuerung umgebaut. 1924: Ändert sich der Eigner in Standard Fruit & Steamship Co. La Ceiba. Das Management bleibt bei Vaccaro Brothers. 1933 erwirbt die Standard Navigation Corp., La Ceiba, das Schiff. und übergibt das Management der Standard Fruit & Steam Ships Co., New Orleans. 1936 wurden die Passagierplätze auf 12 reduziert und gleichzeitig 5 weitere Ladebäume installiert. Am 24.03.1941 verkauft an den griechischen Schiffseigner Nikolaos Konialidis aus Buenos Aires, ein Vetter und Schwager von Aristoteles Onassis, der das Schiff weiterhin unter dem gleichen Namen und Flagge betrieb. Im März 1941 erreichte der Dampfer New York um Reparaturen am Schiff zu erledigen bevor es von North Atlantic & Gulf Steamship Co.in Charter genommen wurde. Die Reparaturen waren nicht geplant und der Charterer war nicht erbaut über die Verzögerungen. Auf Grund dieses Umstandes wurde die Charter um die Hälfte gekürzt und das Schiff machte nur eine Reise für N. A. & G. Der Eigner versuchte das Schiff so schnell als möglich loszuwerden und fand in der schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft einen neuen Käufer. Am 03.07.1941 kaufte das Eidgenössische Kriegs-Transport-Amt (KTA) das Schiff für den Bund und übernahm es in New Orleans. Die Schiffsagentur Honegger & Ascott in London übernahm das Management. Mit dem Eintrag im schweizerischen Schiffsregister am 17.07.1941 erhält es den Namen CHASSERAL und das Rufzeichen: HBDF (Vermessungsdaten: BRT: 2’928, NRT: 2’702, DWT: 3’865). Ende 1941 wird es in Lissabon in der Werft Companhia Uniao Fabril überholt und teilweise umgebaut (neue Vermessung: BRT: 3’128, NRT: 1’874, DWT: 4'064). 60% der Stahlteile des Schiffes wurden damals erneuert. Die Ölfeuerung wurde wieder durch konventionelle Kohlefeuerung ersetzt, da Kohle während des Krieges wesentlich einfacher zu beschaffen war als Marine Fuel oder Dieselöl. Im Laufe des Jahres 1941 brachte die CHASSERAL Getreide von den U.S.A. nach den Mittelmeerhäfen und Schweizer Exportgüter nach den Staaten. In den folgenden zwei Jahren 1942/43 war sie im Pendelverkehr zwischen Lissabon nach Genua, Marseille und Toulon eingesetzt. Die von der Schweizer Regierung gecharterten griechischen Schiffe durften nach dem Kriegseintritt Griechenlands nicht mehr ins Mittelmeer einfahren und mussten ihre Ladung in Lissabon löschen. Am 21.08.1943 lag die CHASSERAL im Hafen von Lissabon, wo sie von dem vom KTA gecharterten griechischen Dampfer MARPESSA eine Ladung Kopra aus Moçambique übernahm. Während des Umladens brach in den Laderäumen 1 und 2 Feuer aus, das von der Besatzung und der Feuerwehr gelöscht werden konnte. Da das Schiff zu kentern drohte, wurde es ausserhalb des Hafens Lissabon im Mar da Palha bei Barreiro auf Grund gesetzt. Allerdings erwies sich diese Massnahme als unbegründet, so dass das Schiff wieder flott gemacht wurde. In 1944 schickte das KTA den Dampfer wieder nach Übersee und er machte zwei Reisen nach Zentralamerika, wo hauptsächlich Kaffee, aber auch andere Produkte geladen wurden. Eine Reise führte nach Philadelphia um eine volle Ladung Getreide abzuholen. Auf einer Fahrt von Marseille nach Lissabon wurde die CHASSERAL am 22.04.1944 vor Sète von britischen Fliegern angegriffen und beschossen, wobei ein Toter und fünf Verletzte zu beklagen waren. Der Dampfer wurde nach Sète eingeschleppt und nach einigen temporären Reparaturen zur permanenten Instandsetzung nach Lissabon gefahren (siehe Bericht unten). Während eines Teils der kritischen Kriegsperiode kommandierte der belgische Kapitän Marcel Henrotin, der 1906 in Sardinien geboren wurde und in der Schweiz lebte, die CHASSERAL. Der ebenfalls belgische Kapitän Louis Jean Van Hoeberghen fuhr auch der Dampfer CHASSERAL vom 06.01.1942 - 18.10.1943, dem 21.11.1943 - 06.02.1944 und dem 06.07.1944 - 27-07 1944. Dazwischen befehligte er auch noch den Dampfer EIGER. Er verbrachte während des 2. Weltkrieges mehr als 2 Jahre auf der CHASSERAL und einen Monat auf der EIGER.

Kapitän Louis Jean Van Hoeberghen Nach dem Krieg fuhr die CHASSERAL weiterhin für das KTA, wobei sie über das ganze Jahr 1945 wieder im Pendelverkehr zwischen Lissabon und den Häfen in Italien und Frankreich eingesetzt war, um die riesigen Schweizer Warenbestände im Hafen von Lissabon abzubauen. In der folgenden Zeit machte sie Reisen nach Brasilien, Westafrika und den U.S.A. Im späten Oktober 1946 lief die CHASSERAL als erstes Schweizer Schiff einen Hafen in Grossbritannien an, sehr zum Erstaunen der Hafenbehörden; die mysteriöse „Swiss Navy“ hatte jetzt die Insel erreicht. Der Frachter nahm in London eine Teilladung von 3500 Tonnen Zement für Brasilien an Bord. Kapitän Henrotin führte noch immer den Dampfer, seine Besatzung bestand hauptsächlich aus Italienern, sowie einigen wenigen Portugiesen und Belgiern, aber nur zwei Schweizern. Ein Messboy war ein gewiefter Bursche aus Westafrika. Eine Delegation von der Schweizer Botschaft besuchte das Schiff und wurde vom italienischen Koch mit einem vorzüglichen Mittagessen bewirtet. Der Bund verkaufte das Schiff am 11.03.1947 für 800'000.- Schweizerfranken an die Nautilus AG, Lugano / Glarus. Die Flagge, Name und Rufzeichen wurden beim Eignerwechsel aber beibehalten (neue Vermessung: BRT: 3’129, NRT: 2’702, DWT: 4'064). Die Reederei setzte den Dampfer hauptsächlich in der Westafrikafahrt ein, jedoch in 1948 bis Anfangs 1949 befand sich das Schiff auf einer Indienreise, wo auch Bombay und Karachi angelaufen wurden. Obwohl das SSA, Schweiz. Seeschifffahrtsamt der Nautilus untersagte, mehr als 12 Passagiere auf ihren Frachtern zu befördern, gab diese Regel auch auf der CHASSERAL Anlass zu Diskussionen und wurde als grober Verstoss gewertet. Zudem beklagte sich eine Zürcher Firma beim Bund über die miese Unterbringung eines ihrer Passagiere an Bord, die eines Schweizer Schiffes unwürdig wäre. Die Nautilus A.G. verkaufte den inzwischen 54-jährigen Dampfer am 08.07.1951 an den Reeder Franco Maresca fu Mariano aus Genua. In einer kleinen Zeremonie im Hafen von Genua wurde am 10.10.1951 um 11:30 die Schweizer Flagge im Beisein eines Konsularbeamten eingeholt und das Schiff dem neuen Eigner übergeben. Von Nautilus war Christian Bach, Bürochef in Genua, die beiden Inspektoren Lisi und Spinella, sowie Kapitän Donato und von der Käuferseite der Reeder Franco Maresca, sein Inspektor Moretti und der neue Kapitän Lavarello an der Übergabe anwesend. Reeder Maresca gab dem Dampfer den Namen MAR CORRUSCO und stellte ihn unter italienischer Flagge in Dienst. 1953 wurde das Schiff zum Abbruch an die Firma A.R.D.E.M. in Savona verkauft. Zusätzliche Informationen und Geschichten Am Samstag den 22.04.1944 morgens, verliess die CHASSERAL den Hafen Marseille mit Ziel Lissabon. Das Kommando führte Kapitän Marcel Henrotin. An Bord hatte sie eine Schweizer Exportladung von nur 361 Tonnen, bestehend aus Maschinenteilen, Uhren und Pharmaprodukten, aber mit einem Wert von ungefähr 9 bis 11 Millionen Schweizerfranken. Zu dieser Zeit war der Süden Frankreichs immer noch von der deutschen Wehrmacht besetzt und das ganze Seegebiet an der französischen Mittelmeerküste befand sich unter der Kontrolle der deutschen Kriegsmarine. Aber die Küste lag auch im Bereich der Alliierten, besonders der Flugzeuge der RAF, die aus Italien, Korsika oder Nordafrika kommend, ihre Angriffe flogen. Die Flugzeuge griffen den Frachter in Wellen von drei Flugzeugen aus geringer Höhe von ungefähr 80 bis 100 Metern mit Bordwaffen und Raketen an. Nachher kehrten sie zurück und flogen einen zweiten Angriff, bevor sie Richtung Süden über dem offenen Meer verschwanden. Dabei wurden der Schweizer Schmierer Maurice Jaccard aus St. Croix (geboren 1909 in Alexandrien) schwer verletzt, so dass er eine Stunde später im Rettungsboot verschied. Fünf portugiesische Seeleute wurden auch verletzt. Die Flugzeuge wurden als britische Bristol Beaufighter Jagdbomber identifiziert. Diese gehörten zur 39. Squadron der RAF, die in Alghero in Sardinien stationiert war. Diese Squadron war auch für die Angriffe auf die MALOJA und die CHRISTINA verantwortlich und sie ist auch heute (2020) noch aktiv mit Predator Dronen.

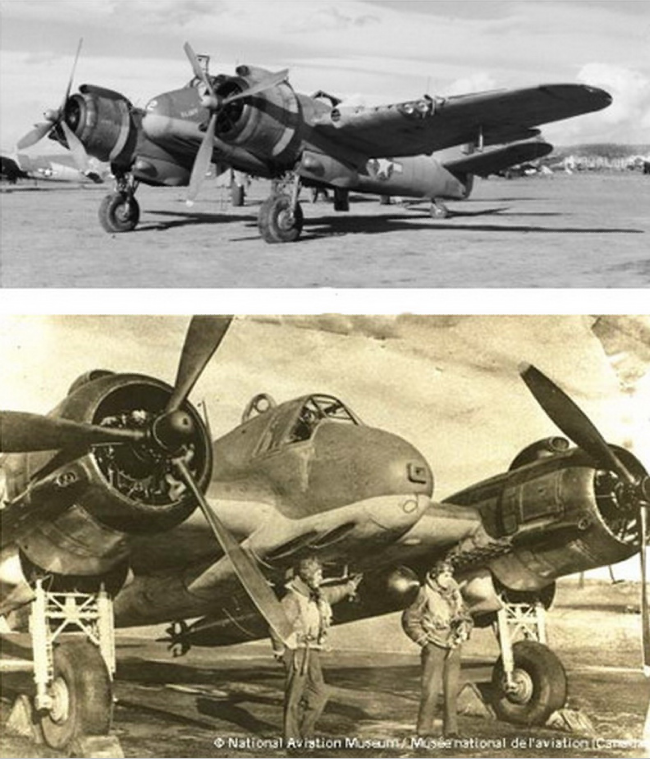

Eine Bristol Beaufighter, wie sie im zweiten Weltkrieg verwendet wurde Britische Freunde vermuteten sogar, dass die Uhren in der Ladung in Wirklichkeit Zeitzünder für Bomben und ähnliche Munition gewesen sein könnten und der Angriff aus diesem Grunde erfolgte. Nun, wenn diese Zünder für die Deutschen bestimmt gewesen wären, dann hätte man sie auf dem Landweg nach Deutschland liefern können, somit wohl eine absurde Idee. Anderseits haben die Briten unsere Schiffe bei jeder Passage in Gibraltar kontrolliert und beide Kriegsparteien erhielten Informationen über die Reisen der Schiffe. Es muss angenommen werden, dass der Führer der Flugzeuge eigenmächtig handelte und eine Fehleinschätzung machte. Auf der Reise nach Lissabon wurde die Besatzung von den Briten über den Vorfall verhört. Grossbritannien stellte seine Verantwortung für den Angriff jedenfalls nicht in Abrede. Das Schiff erlitt viele Einschussschäden auf der steuerbord Seite, auch Brücke und Offiziersunterkünfte wurden schwer beschädigt. Das steuerbord Rettungsboot war zerstört und unbrauchbar. Allerdings scheint es, machten die Laderäume nur wenig Wasser und blieben mehrheitlich trocken, aber gemäss einer Schadensliste erlitt auch die Ladung teilweise schwere Schäden. Den grössten Schaden wohl verursachte eine 8 cm Raketenbombe, so die Beschreibung der Kriegsmarine, die durch die Bordwand in den Maschinenraum eindrang und im Dampfkondensator der Hauptmaschine explodierte, worauf der Maschinenraum bis über die Zylinder geflutet wurde. Die Explosion dieses Geschosses schleuderte den Schmierer Maurice Jaccard mit unheimlicher Wucht gegen die Standsäule des Mitteldruckzylinders der Hauptmaschine, dabei erlitt er schwerste Verletzungen am Kopf und am linken Bein. Nachdem die Maschine gestoppt und die Feuer in den Kesseln gelöscht waren, befahl der Kommandant den steuerbord Anker fallen zu lassen. Dann verliessen die Besatzung und der Kapitän das Schiff im unversehrten backbord Rettungsboot um nicht weitere Angriffe zu provozieren. Nach zwei Stunden nahm das Patrouillenboot FSE-04, ein Hafenschutzboot der Deutschen Kriegsmarine die Besatzung an Bord und fuhr zunächst zurück zur CHASSERAL. Das Schiff hatte jetzt starke steuerbord Schlagseite und im Maschinenraum stand das Wasser 3 Meter hoch. Auch Laderaum 3 machte Wasser. Der Kapitän und seine Offiziere glaubten, das Schiff wäre unwiederbringlich verloren und um 21:30 gingen sie wieder an Bord des Patrouillenbootes und wurden um 02:00 in Sète an Land in Sicherheit gebracht. Ohne Auftrag vom Kapitän versuchte die in Marseille stationierte 6. Sicherungsflotille der deutschen Kriegsmarine mittlerweile die CHASSERAL zu bergen. Mehrere Schiffe beteiligten sich an dieser Bergung, unter anderem auch das Geleitboot M-6031, welches die schwer beschädigte CHASERAL in Richtung Sète schleppte und nach ungefähr 4 ¾ Stunden Schleppfahrt die CHASSERAL nordöstlich vom Hafen Sète auf Grund setzten konnte. Bei dieser Rettungsaktion ging anscheinend auch ein neueres deutsches Seenotflugboot Dornier DO24 verloren, das dicht neben der CHASSERAL in den Fluten versank. Allerdings hatte niemand von der Besatzung dieses Flugboot gesehen und sein Verlust geschah unter sehr mysteriösen Umständen. Die ganze Bergung dauerte 11 Stunden und stand unter dem Kommando des Korvettenkapitäns Hermann Polenz.

Korvettenkapitän H. Polenz (rechts) mit einem der vielen Admiräle jener Zeit

H. Polenz (2. von links) im Gespräch mit seinen Offizieren Der tote Schweizer Maurice Jaccard wurde am 25.04.1944 auf dem Friedhof von Sète im Beisein des Kapitäns und der gesamten Besatzung beigesetzt. Er war der erste und einzige Schweizer Seemann der im 2. Weltkrieg durch kriegerische Einwirkung ums Leben kam (siehe Bericht unten). Die Ladung transferierte man auf die ZÜRICH zum Weitertransport nach Lissabon. Nach einer behelfsmässigen Reparatur in Sète konnte das Schiff am 07.06.1944 den Hafen wieder verlassen und seine Reise nach Lissabon fortsetzen, wo es am 12.06.1944 eintraf. Nach einer ordentlichen Reparatur bei der Werft Companhia Uniao Fabril, die bis zum 31.07.1944 dauerte, konnte die CHASSERAL ihren normalen Dienst wieder aufnehmen. Ungefähr zur selben Zeit attackierten britische Flugzeuge zwei Rotkreuzschiffe im selben Seegebiet, die EMBLA sank am 19.04.1944 und die CHRISTINA wurde am 06.05.1944 beschädigt. Die deutsche Kriegsmarine verlangte einen Bergelohn von 25 % des Wertes des Schiffes und der Ladung, sowie 1,3 Mio. Schweizerfranken als Vergütung für das verlorene Seenotflugboot. Die Schweizer Behörden hinterfragten auch den Einsatz dieses Flugbootes zur Rettung eines treibenden, unbemannten Schiffes, eine Antwort dazu fanden wir weder in Bern, noch in deutschen Archiven, es wird vermutet, dass wichtige Unterlagen in den Kriegswirren verloren gingen. Ob die Verhandlungen mit Deutschland erfolgreich abgeschlossen werden konnten, entzieht sich unserer Kenntnis, zumal das Deutsche Reich ein Jahr später in Schutt und Asche versank.

Ein Flugboot Dornier DO24, das im zweiten Weltkrieg, aber auch nach dem Kriege zur Seenotrettung verwendet wurde Letztendlich wollten die an der Bergung beteiligten deutschen Seeleute noch eine Uhr als Andenken und Geschenk erhalten. Nachdem unsere Behörden dieses Geschenk als politisch problemlos eingestuft hatten, ermächtigten sie die Schweizerische Rückversicherung dazu (sie betreute die Kriegsversicherung), die Geschenke zu machen. Ob die Seeleute ihre Uhren tatsächlich erhalten haben, konnte nicht mehr festgestellt werden. Verstorbene Seeleute im Dienste der Schweiz während des 2. Weltkrieges Während des 2. Weltkrieges sind im Dienste der Schweizer Seefahrt, eingeschlossen der gecharterten Schiffe einige Seeleute durch direkte Kriegseinwirkung um ihr Leben gekommen. Maurice Jaccard war jedoch der einzige Schweizer der auf diese Weise sein Leben verlor. Andere Schweizer sind aber bei Unfällen an Bord ums Leben gekommen, die jedoch mit dem Kriegsgeschehen nichts zu tun hatten. Der grösste Verlust mit 30 Todesopfern betraf den vom KTA gecharterten, griechischen Dampfer MOUNT LYCABETTUS, der im März 1942 nach dem Auslaufen aus Baltimore spurlos verschwand. Erst nach Beendigung des Krieges konnte aus deutschen Dokumenten und Logbüchern entnommen werden, dass das Schiff vom deutschen U-373 (Kommandant Paul-Karl Loeser) am Nachmittag des 17.03.1942 mit zwei Torpedos versenkt worden ist. Am 7. September 1943 versenkten britische Flieger bei Korsika den Frachter MALOJA, wobei drei portugiesische Seeleute ums Leben kamen, während der 1. Offizier, ein Holländer und ein Schweizer Koch schwer verwundet wurden. Wieder ein Jahr später, am 19. September 1944 musste die GENEROSO im Hafen von Marseille verholen. Bei diesem Manöver am Mittag lief sie auf eine Treibmine, die sie mittschiffs traf und versenkte. Bei der schweren Explosion wurden der weissrussische Kapitän Anatol Gouretzky und der Schweizer Bordfunker Christian Schaaf in die Luft und über Bord geschleudert. Während der Kapitän dabei sein Leben verlor, fiel der Bordfunker mit brennenden Kleidern ins Wasser und konnte schwer verletzt gerettet werden. Bemerkungen zu Angriffen auf neutrale Schiffe In englischen Teil unserer Geschichte haben wir noch einige Bemerkungen aus dem Buch “The Armed Rovers: Beauforts and Beaufighters over the Mediterranean”, von Roy Conyers Nesbit (Casemate Publishers, 2014) zitiert. Wir möchten diese Zeilen jedoch nicht übersetzen, aber dennoch festhalten, dass die Piloten den Befehl erhielten, jedes Schiff in dem fraglichen Seegebiet sofort anzugreifen und zu versenken. SwissShips HPS, MB, Januar 2020 Quellen:

|

![]()

Histoire du navire

Ce cargo à vapeur fut lancé le 20.08.1897 au chantier naval écossais Scottish Shipyard Hall, Russel & Co., Aberdeen (coque no. 303). Terminé et baptisé INGELI, le navire sera délivré à l'armateur John T. Rennie & son, Aberdeen, en octobre 1897 (No. Officiel 108651, indicatif d'appel PVJD). Le vapeur était propulsé par une machine à vapeur triple expansion de 1810 CH, construite par ce même chantier Naval. La vitesse du navire était de 12 noeuds ce qui était remarquable en ce temps là. A l'origine, le bateau était aussi gréé de voiles auxiliaires. Le bateau offrait aussi de la place en cabine pour 36 passagers. Pour la cargaison, il était armé de 3 mâts de charge. En 1911, le vapeur sera vendu à Charente Steamship Co., Ltd, Liverpool et le management sera confié à Thos. & Jas. Harrison, Liverpool. En 1913, il est racheté par la compagnie Hondurienne Vaccaro Brothers Ltda, La Ceiba, re-baptisé TEGUCIGALPA et immatriculé sous pavillon Hondurien. (indicatif d'appel HRBB) En avril 1920, la Tegucigalpa devint le nouvel armateur alors que l'ancien armateur devint le manager du navire. En même temps, l'allumage de la chaudière passa du charbon au fuel. En 1924, changement de propriétaire à nouveau : Standard Fruit & Steamship Co., La Ceiba. Le management reste le même. En 1933, la Standard Navigation Corp., La Ceiba achète le vapeur et donne le management à la Standard Fruit & Steamships Co., New Orleans. En 1936, la capacité de passagers est réduite à 12 et, en même temps on installe 5 mâts de charge supplémentaires. Le 24.03.1941, revendu à l'armateur grec de Buenos Aires, un cousin et aussi un beau frère de Aristoteles Onassis, qui continua d'opérer le navire avec les mêmes nom et pavillon. En mars 1941, le vapeur arrive à New York pour réparations avant d'être affrété par la North Atlantic & Gulf Steamship Co. Les réparations se retardèrent ce dont les affréteurs furent mécontents. Suite à ces circonstances, l'affrètement fut raccourci et le navire ne fit en fait qu'un seul voyage pour la N.A & G. L'armateur essaya de vendre son navire au plus vite et trouva un acheteur en la personne de la Confédération Helvétique ! Le 03.07.1941, l' OGT, Office de Guerre pour les Transports en cas de Guerre acheta le vapeur et en pris possession à La Nouvelle Orleans. L'agence maritime Honegger & Ascott de Londres pris en charge le management. Immatriculé sous pavillon suisse le 17.07.1941, il est re-baptisé CHASSERAL avec indicatif d'appel HBDF (il est alors re-jaugé : 2928 tonnes brutes, 2702 tonnes nettes et 3865 tonnes de port en lourd). A la fin de 1941, le navire sera révisé et partiellement reconstruit à Lisbonne au chantier naval Companiha Uniao Fabril, et re-jaujé à nouveau : 3128 tonnes brutes, 1874 tonnes nettes et 4064 tonnes de port en lourd. Environ 60% de l'acier du navire fut remplacé. La combustion fut à nouveau changée de fuel au charbon car le charbon, en ce temps là, était plus facile à obtenir que le fuel. Durant 1941, le CHASSERAL transporta des céréales des USA vers des ports méditerranéens et retournait aux States avec de la cargaison d'export suisse. En 1942/43, il fut utilisé comme navette entre Lisbonne et Gène, Toulon et Marseille. Les navires grecs affrétés par le gouvernement suisse n'étant plus autorisés à entrer en Méditerranée et devaient décharger leur cargaison d'outremer dans le port de Lisbonne. Le 21.08.1943, le CHASSERAL était dans le port de Lisbonne, chargeant une cargaison de copra (fibre de noix de coco) du cargo grec MARPESSA (aussi en affrètement par la confédération) quand un feu se déclara dans les cales 1 et 2. Le feu put être maitrisé par l'équipage et les pompiers portugais. De peur que le navire ne chavire, du à la quantité d'eau giclées dans les cales pour éteindre le feu, il fut décidé d'échouer le bateau hors du port, à Barreiro. Cette mesure se révélant infondée, le navire fut renfloué à nouveau. En 1944, le navire fut expédié à nouveau outremer et fit 2 voyages en Amérique centrale, chargeant surtout du café mais aussi d'autres produits. Un voyage, il fut envoyé à Philadelphie pour une pleine cargaison de céréales. Pendant un voyage de Marseille à Lisbonne, le 22.04.1944, le CHASSERAL fut attaqué par des chasseurs britanniques de combat au large de Sète et, après des réparations sommaires, il put continuer son voyage vers Lisbonne où des réparations permanentes furent effectuées. Durant une partie critique de la guerre, le capitaine belge Marcel Henrotin, né en 1906 en Sardaigne et habitant en Suisse a conduit le valeur CHASSERAL. Le capitaine Louis Jean van Hoeberghen, également belge, a lui aussi conduit le CHASSERAL du 06-01-1942 au 18-10-1943, puis du 21-11-1943 au 06-02-1944 et finalement du 06-07-1944 au 27-07 1944. Entretemps il a également servi sur le vapeur EIGER. Il passa ainsi pendant la seconde guerre mondiale plus de deux ans aux commandes du le CHASSERAL et un mois sur le EIGER.

Capitaine Louis Jean Van Hoeberghen Après la guerre, le Chasseral continua de naviguer pour l'OGT. Durant 1945, il transporta du cargo de Lisbonne vers des port français et italiens pour être ensuite être re-dirigés vers la Suisse. C'était nécessaire car d'énormes quantités de cargaisons s'étaient accumulées à Lisbonne. L'année suivante fut passée avec des voyages vers le Brésil, l'Afrique Equatoriale et les USA. Fin octobre 1946, le CHASSERAL fut le premier navire suisse à escaler dans un port anglais, au grand amusement des autorités locales qui découvraient cette mystérieuse marine suisse. Le navire arriva à Londres pour charger du ciment pour le Brésil. Le capitaine Henrotin était toujours aux commandes. L'équipage se composait surtout d'italiens mais aussi de portuguais, de belges mais seulement de deux suisses. Le messboy était africain. Une délégation de l'ambassade de Suisse visita le navire et apprécièrent le bon repas préparé par le cuisinier italien. Le 11.03 1947, le gouvernement fédéral vendit le navire, pour 800'000.- Fr à la compagnie Nautilus AG de Lugano et Glaris. Le nom, le pavillon et l'indicatif d'appel ne changèrent pas, seulement les tonnage : 3129 tonnes brutes, 2702 nettes et 4064 de port en lourd. La nouvelle compagnie utilisa le navire surtout sur l'Afrique équatoriale mais, de 1948 jusqu'au début 1949, le vapeur entrepris un voyage vers le sous-continent, divers ports en Inde et au Pakistan. Bien que l'Office Suisse de la Navigation Maritime ne permettait pas d'embarquer plus que 12 passagers, règle que la Nautilus ne suivit pas et cela donna lieu à des discussions et des ennuis. En plus, une compagnie de Zürich vint se plaindre que les cabines du navires n'étaient pas à la hauteur et pas selon les standards d'un navire sous pavillon suisse. La Nautilus AG vendit le vieux vapeur de 54 ans le 08.07.1951 à l'armateur génois Franco Maresca Fu Mariano. Une petite cérémonie eu lieu à Gènes quand le pavillon suisse fut amené une dernière fois sur ce navire, le 10.10.1951 à 11:30h, en la présence d'un officier consulaire suisse. De Nautilus, Christian Bach, Chef du bureau de Nautilus à Gènes, les deux inspecteurs Lisi et Spinella et le commandant Donato. Du côté nouvel armateur, le propriétaire Franco Maresca, son inspecteur Moretti et le nouveau commandant, le capitaine Lavarello. Le navire fut rebaptisé MAR CORRUSCO et fut immatriculé sous pavillon italien. En 1953 le navire fut vendu à la démolition à la compagnie A.R.D.E.M. à Savone. Informations supplémentaires et anecdotes Raid aérien au large de la côte française le 22.04.1944 Sous le commandement du capitaine Henrotin, le CHASSERAL appareilla de Marseille un samedi matin, le 22.04.1944, à destination de Lisbonne. La cargaison de seulement 361 tonnes mais haute en valeur car consistant de pièces de mécaniques de précision, de montres, produits pharmaceutiques, le tout d'une valeur d'une dizaine de million de francs. A cette époque, le sud de la France était encore occupé par la marine et les troupes allemandes. Mais atteignables par les forces alliées, surtout par les chasseurs de la RAF basés en Italie, Corse et Afrique du nord. Pendant que le Chasseral naviguait cap à l'ouest au large de l'embouchure du Rhone, 8 ou 10 avions chasseurs anglais attaquèrent le navire sur son tribord peu après 17:00h à 15 miles nautiques au large du port de Sète à la position 43° 22.5' N 004° 05' E. L profondeur de la mer était de 53 m, le temps était au beau et la visibilité bonne. Les signes de neutralité furent ignorés par les aviateurs : pavillons suisse, le mot « SWITZERLAND » peint sur les flancs du navire, croix suisse sur la cheminée et sur le pont. Les avions attaquèrent pas vagues de trois, à basse altitude, 80 à 100 m, avec leur canons et bombes. Il y eu deux attaques avant qu'ils disparaissent au large. Ils furent identifiés comme étant des British Bristol Beau Fighters, des chasseurs/bombardiers bien connus. Ces appareils faisaient partie du RAF 39 Squadron qui opérait depuis Alghero en Sardaigne. Ce même Squadron était aussi impliqué dans les attaques des MALOJA et CHRISTINA. Cette unité opère encore aujourd'hui, mais avec des drones d'attaque. Le marin, graisseur, suisse Maurice Jaccard de St Croix /VD fut grièvement blessé et décéda lors de son transfert à terre par embarcation de sauvetage. Cinq marins portugais furent aussi blessés mais

Un Bristol Beaufighter, utilisé par la RAF pendant la 2nde guerre mondiale Les britanniques apparemment suspectèrent que les montres de la cargaison étaient en fait des détonateurs de bombes ou du genre et ce fut apparemment la raison du raid. Mais, en fait, cela aurait été ridicule car les « montres » pu être acheminées directement en Allemagne par la route ou le rail ! Mais aussi, les anglais/alliés étaient parfaitement informés de tous les transport sur les navires suisses, les navires étaient aussi toujours contrôlés en passant Gibraltar ! Le navire fut sévèrement touché sur les flancs de la coque à tribord. Les superstructures furent aussi très touchées, passerelle et cabines des officiers. L' embarcation de sauvetage tribord fut totalement détruite. Les cales demeurèrent quasiment sèches car l'impact des bombes touchèrent la coque au dessus de la ligne de flottaison. Par contre, une bombe entra dans la salle des machines, explosant près du condensateur et la salle des machines se remplit d'eau jusqu'en haut des cylindres du moteur. Le souffle de l'explosion poussa brutalement le graisseur Maurice Jaccard contre le moteur, le blessant grièvement à la tête et aux jambes. Après que le moteur fut stoppé et le début d'incendie maitrisé, le commandant ordonna de mouiller l'ancre tribord. Ensuite, tout l'équipage quitta le navire dans l'embarcation de sauvetage bâbord pour ne pas être exposé à une éventuelle nouvelle attaque. Après deux heures d'attente, la vedette portuaire FSE-04 de la marine allemande embarqua l'équipage et le ramena sur le Chasseral. Le navire montrait une gîte importante maintenant et il y avait trois mètres d'eau dans la salle des machines. Un peu d'eau fut alors aussi notée dans la cale 3. Le commandant jugea que le navire était définitivement perdu et, à 21:30h, tout le monde embarqua à nouveau sur la vedette allemande pour être amené à Sète où ils arrivèrent é 2 heures du matin cette nuit là. Sans en référer au capitaine Henrotin, le commandement de la 6ème flottille de sécurité de la marine allemande essaya de sauver le CHASSERAL. Plusieurs navires prirent part à l'opération de sauvetage, entre autres le navire d'escorte M-6031. Ils réussirent de ramener, après 4.5 heures de remorquage, le navire à Sète où il fut échoué en sécurité sur fond de sable au NE du port de Sète.

Lieutenant Commander H. Polenz (à droite) avec un amiral de la flotte allemande

Hermann Polenz (2ème de la gauche) parlant à ses officiers Le marin graisseur suisse Maurice Jaccard fut enterré le 25.04.1944 au cimetière de Sète, en présence du commandant et de tout l'équipage. Ce marin fut le premier et le seul marin suisse à décéder suite à une action militaire durant la seconde guerre mondiale (voir rapport ci-dessous) La cargaison du navire fut transférée sur le navire ZURICH pour destination Lisbonne. Après quelques réparations temporaires à Sète, le CHASSERAL fut capable d'appareiller de Sète, le 07.06.1944 et continua son voyage vers Lisbonne où il arriva le 12.06.1944. Après les réparations permanentes au chantier naval Companhia Uniao Fabril, terminées le 31.07.1944, le vapeur put reprendre son service régulier. A la même époque, des avions anglais bombardèrent 2 navires de la croix rouge, l'un était le EMBLA sous pavillon suédois qui coula le 19.04.1944 et l'autre était le CHRISTINA sous pavillon espagnol qui fut seulement endommagé, le 06.05.1944. Bien sûr, ce raid sur le CHASSERAL provoqua des suites légales, qui durèrent plusieurs années. La confédération résumèrent nos revendications monétaires pour les dommages au navire et à sa cargaison une somme de 2.7 millions de Fr à l'intention du gouvernement britannique. Après de dures négociations, les anglais acceptèrent de payer 50'000.- £ , l'équivalent de 867'000.- de nos francs. La marine allemande, elle, demanda une compensation de 25% de la valeur du navire et sa cargaison. Pratique normale dans la marine marchande en cas de sauvetage. Les allemands demandèrent aussi une compensation de 1.3 million de Fr pour la perte de l'hydravion ... que personne n'avait vu sur la scène de l'attaque et du sauvetage ! Les suisses demandèrent une explication : qu'aurait pu bien faire un hydravion dans ce cas là ? L'équipage était en sécurité sur la vedette allemande, la mer était calme et le navire en remorque vers le port de Sète. Nous n'avons retrouvé aucune archive mentionnant une réponse à cette question... On peut penser que beaucoup de documents furent perdus dans ce temps pour le moins chaotiques de fin de guerre.)

Un hydravion de sauvetage allemand, Dornier DO24, utilisé pendant la seconde guerre mais aussi ultérieurement Les marins allemands ayant participé aux opérations de sauvetage demandèrent s'ils pouvaient recevoir une montre suisse en souvenir de leur actions. Les autorités suisses classifièrent cette demande comme sans problème, politiquement, et autorisèrent l' « assurance de guerre » de donner suite à cette demande. Nous n'avons pas pu retrouver de document attestant que les marins reçurent vraiment leur montres... Décès de marins sur des navires suisses pendant la seconde guerre Mondiale Durant la seconde guerre mondiale, quelques marins de navires sous pavillon suisse ou étrangers affrétés La plus importante perte humaine quand le navire MOUNT LYCABETTUS disparut sans laisser de trace avec 30 hommes à bord en mars 1942. Ce navire grec, affrété par le gouvernement suisse, était en route de Baltimore vers l'Europe et, après quelques jours n'envoya plus de messages de position. Le 07.09.1943, des avions chasseurs anglais attaquèrent et envoyèrent par le fond le navire MALOJA au large des côtes corses. Trois marins portugais perdirent la vie et le 1er officier hollandais, ainsi que le cuisinier suisse furent grièvement blessés De nouveau, une année plus tard, le vapeur suisse GENEROSO fut, pendant une manoeuvre portuaire, touché par une mine dérivante. La forte explosion souffla littéralement le commandant Anatol Gouretzki et l'officier radio suisse Christian Schaaf dans les airs ! Le commandant perdit la vie tandis que le radio fut projeté par dessus bord, ses habits en flammes, et tomba à la mer d'où le pu être repêché, blessé et brulé. Observations à propos des attaques sur des navires neutres Dans le texte anglais de notre histoire, nous citons quelques observations tirées du livre « The armed Rovers : Beauforts and Beau fighters over the Mediterranean » de Roy Conyers nesbit (Casemate Publishers. 2014). Nous n'aimerions pas traduire ces quelques lignes. Néanmoins, nous devons relever le fait que les pilotes avaient l'ordre d'attaquer immédiatement tout navire navigant dans des parages suspects. SwissShips HPS, FG, MB, Janvier 2020

Sources :

|

![]()

Cronistoria delle navi

Varata il 20-08-1997, ultimata nel cantiere scozzese Hall, Russel & Co., Aberdeen nell’ottobre del 1897 con il nome INGELI (numero di costruzione 303) e consegnata alla proprietaria John T. Rennie and Son, Aberdeen (numero matricola: 108651, nominativo internazionale: PVJD). La nave viene propulsa da una macchina a vapore a triplica espansione della Hall, Russel & Co., Aberdeen, (1810 Cv) permettendo una velocità considerevole per quel periodo di 12 nodi. Inoltre era in attrezzata di ospitare 36 passeggeri. Inizialmente la nave era armata di pennoni sistemati sull’albero di prua per utilizzare delle vele ausiliarie per il sostegno al propulsore. I mezzi di carico sono composti da tre alberi. La parola INGELI proviene dalla lingua Zulu e significa freddo, neve o nevischio, inoltre è il nome di un monte a KwaZulu-Natal. Nel 1911 ceduta alla Charente Steamship Co. Ltd. Di Liverpool, la quale la dal in gestione alla Thos. & Jas. Harrison, Liverpool. Nel 1913 viene eseguita la vendita alla hondurenia Vaccaro Brothers Ltda., La Ceiba, nominandola TEGUCIGALPA. Con l’immatricolazione sotto la bandiera della Honduras le viene assegnato il nominativo internazionale: HRBB. Nell’aprile 1920 la Tegucigalpa Steamship Corporation diveta nuova proprietaria, mentre la Vaccaro Brothers Ltda. Si occupa della gestione. Contemporaneamente il propulsore viene convertito da alimentazione a carbone a olio combustibile. 1924: la proprietaria cambia in Standard Fruit & Steamship Co. La Ceiba. La gestione rimane alla Vaccaro Bros. La Standard Navigation Corp. La Ceiba aquisisce la nave nel 1933 e la dal in gestione alla Standard Fruit & Steam Ships Co. New Orleans.Nel 1936 la capacità dei passeggeri è stata ridotta a 12 persone e nello stesso tempo installati altri 5 bighi per la movimentazione dei carichi. Il 24-03-1941 ceduta all’armatore greco Nikolaos Konialidis (cugino e cognato di Aristoteles Onassis) di Buenos Aires, il quale la impiega con lo stesso nome e bandiera. Nel marzo 1941 la nave arriva a New York per eseguire lavori di manutenzione prima che la North Atlantic & Gulf Steamship la prende a noleggio. Non si trattava di riparazioni programmate ed il noleggiatore non era compiaciuto dell’indugio. Per tale causa il nolo viene dimezzato e la nave esegue appena un viaggio per la N. A. & G. La proprietaria cerca di sbarazzarsi il più presto possibile del mezzo e nella Confederazione Svizzera trova un nuovo aquirente. Il UGT (Ufficio di Guerra per i Trasporti) reparto trasporti in guerra confederale aquista la nave il 03-07-1941 per la confederazione e la prende in consegna a New Orleans. L’agenzia Honegger & Ascott di Londra si occupa della gestione. Con l’immatricolazione nel registro delle navi svizzere il 17-07-1941, le viene assegnato il nome CHASSERAL ed il nominativo internazionale: HBDF (stazzatura: TSL: 2928, TSN: 2702, DWT: 3865). Alla fine del 1941 viene revisionata a Lisbona nel cantiere Companhia Uniao Fabril e parzialmente ristrutturata (nuova stazzatura: TSL: 3128, TSN: 1874, DWT: 4064). Il 60% delle strutture metalliche vengono sostituite. L’alimentazione ad olio combustibile viene riportata a quella tradizionale a carbone, più facilmente reperibile del Marine Fuel o Diesel durante il conflitto mondiale. Nel corso dell’anno 1941 la CHASSERAL trasporta grano dagli Stati Uniti verso porti del Mediterraneo e merce d’esportazione Svizzera verso gli Stati. Nei due anni seguenti 1942/43 è impiegata nel traffico pendolare tra Lisbona e Genova, Marsiglia e Tolone. Dato le circostanze belliche, dopo l’entrata nella guerra della Grecia, le navi greche noleggiate dal governo Svizzero non potevano più entrare nel Mediterraneo ed erano costrette a scaricare le merci a Lisbona Il 21-08-1943 la CHASSERAL è ormeggiata nel porto di Lisbona dove viene trasbordato un carico di copra proveniente dal Moçambique dalla nave greca MARPESSA nolleggiata dal UGT. Durante il trasbordo scoppia un’incendio nelle stive 1 e 2, il quale viene estinto dall’equipaggio e dai vigili del fuoco. Dato che la nave si poteva capovolgere, viene arenata fuori dal porto di Lisbona nel Mar da Palha nei pressi di Barreiro. Tuttavia tale azione risultva infondata cosichè la nave viene rimessa in sesto. Nel 1944 il UGT invia la nave nuovamente oltreoceano eseguendo due viaggi verso il Centroamerica, dove principalmente erano stati caricati caffè ed altri prodotti. Un viaggio la eseguiva verso Philadelphia per imbarcare un carico completo di grano. Durante un viaggio da Marsiglia a Lisbona, il 22-04-1944 la CHASSERAL viene attaccata e colpita con spari da velivoli inglesi antistante Sété, provocando un morto e cinque feriti. La nave viene rimorchiata a Sété e dopo alcune riparazioni provvisorie si reca a Lisbona per eseguire le necessarie riparazioni (vedi relazione più in basso). Durante l’intero difficile periodo del conflitto il comandante belga Marcel Henrotin, nato nel 1906 in Sardegna e domiciliato in Svizzera, era il comandante della CHASSERAL. Come sostituto di M. Henrotin funge il Comandante Louis Jean Van Hoeberghen, anche lui belga. Era imbarcato dal 06-01-1924 – 18-10-1943, dal 21-11-1943 – 06-02-1944 e dal 06-07-1944 – 27-07-1944 sulla nave a vapore CHASSERAL. Frattanto comandava anche la nave a vapore EIGER. Durante il secondo conflitto mondiale trascorre oltre due anni sulla CHASSERAL e un mese sulla EIGER.

Comandante Louis Jean Van Hoeberghen Dopo la guerra, la CHASSERAL continuava a fare viaggi per il UGT, dove nuovamente era ingaggiata nel traffico pendolare tra Lisbona e porti italiani e francesi per ridurre le enormi scorte di merci immagazzinate nel porto di Lisbona. Nel periodo successivo esegue anche viaggi verso il Brasile, Africa dell’Ovest e Stati Uniti. Nel tardo ottobre del 1946, la CHASSERAL approda in un porto britannico come prima nave Svizzera e le autorità portuali erano stupiti; la misteriosa “Swiss-Navy” ora ha raggiunto la loro isola. La nave imbarca un carico parziale di 3500 tonnelate di cemento diretto in Brasile. Il comandante Henrotin era sempre ancora al comando, il suo equipaggio era composta in maggioranza da italiani, come anche alcuni portoghesi e belgi, ma solamente due Svizzeri. Un piccolo di camera era un’africano dell’Ovest molto sveglio. Una delegazione dell’Ambasciata Svizzera visitava la nave ed era stata ospitata con un eccezionale pranzo preparato dal cuoco italiano. Dopo il conflitto, la confederazione vende la nave per 800'000 Franchi Svizzeri il 11-03-1947 alla Nautilus AG, Glarus. Bandiera, nome e nominativo internazionale rimangono invariati dopo il cambio di proprietà (nuova stazzatura: TSL: 3129. TSN: 2702, DWT: 4064). La compagnia principalmente immette la nave nel servizio verso l’Africa dell’Ovest, tuttavia nel 1948 fino inizio 1949 la nave effetua un viaggio verso l’India, dove vengono approdati i porti di Bombay e Karachi. Nonostante l’interdizione da parte dell’USNM (Ufficio svizzero della navigazione marittima) alla Nautilus, di trasportare più di 12 passeggeri sulle sue navi, anche sulla CHASSERAL questa regolamentazione dava motivo a discussioni e valutato come una grave trasgressione. Inoltre una ditta di Zurigo si lamentava presso la confederazione della scarsa sistemazione a bordo di uno dei loro passeggeri, indegna per una nave svizzera. La Nautilus A.G. il 08-07-1951 cede la nave con ormai 54 anni di vita alla Franco Maresca fu Mariano di Genova. Durante una piccola cerimonia nel porto di Genova, alle 11.30 del 10-10-1951, in presenza di un’impiegato consolare viene ammainata la bandiera svizzera e la nave consegnata alla nuova proprietaria. Da parte della Nautilus erano presenti Christian Bach, capoufficio a Genova, i due ispettori Lisi e Spinella, come anche il com.te Donato, dal lato dei nuovi proprietari invece l’armatore Franco Maresca, il suo ispettore Moretti e il nuovo comandante Lavarello. L’armatore Maresca nomina MAR CORRUSCO la sua nuova nave e la mette in servizio sotto bandiera italiana. Nel 1953 ceduta alla A.R.D.E.M. di Savona per demolizione. Ulteriori informazioni e storie Il sabato mattina del 22-04-1944, la CHASSERAL parte dal porto di Marsiglia per raggiungere Lisbona. Il comando era affidato a Marcel Henrotin. A bordo si trovava un carico di esportazione di appena 361 tonn., composto da macchinari, orologi e prodotti farmaceutici, ma con un valore di 9 a 11 milioni di Franchi Svizzeri. La parte meridionale della Francia allora era ancora occupata dalla Wehrmacht tedesca e l’intera area di mare delle coste mediterranee francesi sotto controlla della Marina Militare tedesca. Ma la costa era anche un settore degli alleati, specialmente della RAF, la quale dall’Italia, Corsica o Africa del Nord eseguiva i propri attacchi. Metre la CHASSERAL si dirigeva verso ovest a sud della foce del fiume Rodano sulla rotta prescritta, da 8 a 10 caccia provenienti dall’entroterra attaccavano la nave alle 17.10 sul lato di dritta. L’attacco veniva effettuato in posizione 43° 22’ 30’’ nord / 004° 05’ 00’’ est a circa 6 miglia a sud di Pointe Espiquettes e a circa 15 miglia a est di Sété. Il fondale in tale posizione era di 53 metri. Il tempo era bello con visibilità buona. Inoltre erano state ripitturate in porto a Marsiglia le insegne di guerra, cioè la bandiera svizzera in coperta e sulle fiancate come anche la scritta “Switzerland”, ed erano ben visibile. Dopodichè tornavano indietro eseguendo un secondo attacco, prima di scomparire in direzione sud verso il mare aperto. In tale contesto l’ingrassatore svizzero Maurice Jaccard di St. Croix (nato nel 1909 ad Alessandria) viene gravemente infortunato, decedendo un’ora più tardi nella scialuppa di salvataggio. Anche cinque marittimi portoghesi riportano delle lesioni. Gli aerei venivano identificati come caccia Bristol Beaufighter britannici. Questi appartenevano alla 39esima squadra della RAF, la quale era stazionata ad Alghero in Sardegna. Questa squadriglia inoltre era anche responsabile degli attacchia alla MALOJA e Christina e tuttora (2020) è attiva con drone predator.

Un Bristol Beaufighter, come veniva utilizzato nel secondo conflitto Amici britannici presumono persino, che gli orologi facendo parte del carico in realtà fossero inneschi a tempo per bombe o munizioni simili e perciò era stato eseguito l’attacco. Comunque, se questi inneschi fossero destinati ai tedeschi, allora la consegna si poteva eseguire via terra, perciò un’idea assurda. D’altra parte, gli inglesi ad ogni passaggio delle nostre navi a Gibilterra, erano state controllate e tutte e due le parti ricevevano informazioni sui viaggi delle navi. È da presumere che il comandante degli aerei aveva agito di propria iniziativa e valutato male la situazione. Durante il viaggio verso Lisbona, l’equipaggio era stato interrogato dai britannici sull’accaduto. La Gran Bretagna non aveva negato la responsabilità dell’attacco. La nave aveva subito parecchi danni dai proiettili su lato di dritta, anche il ponte di comando e gli alloggi degli ufficiali erano stati danneggiati gravemente. La lanca di salvataggio di dritta era stata distrutta e inutilizzabile. Tuttavia sembra che nelle stive entrava poca acqua e in generale rimanevano asciutte, ma secondo un elenco dei danni il carico aveva subito gravi danni. Il danno maggiore aveva provocato un ordigno da 8 cm, così la descrizione della Marina Militare, il quale aveva attraversato la lamiera della fincata entrando nella sala macchine dove esplose nel condensatore del vapore del motore principale, provocando l’allagamento fin sopra i cilindri. L’esplosione dell’ordigno scaraventava l’ingrassatore Maurice Jaccard con violenza contro il puntello del cilindro a media pressione del motore principale, subendo gravi lesioni sulla testa e gamba sinistra. Quando poi la macchina era stata fermata ed il fuoco nelle caldaie si era estinto, il comandante ordinava di dare fondo all’ancora di dritta. Per non provocare ulteriori attacchi, l’equipaggio ed il comandante avevano abbandonato la nave con la lanca di salvataggio di sinistra intatta. Dopo due ore il pattugliatore FSE-04 della Marina Militare tedesca recupera l’equipaggio e lo riporta a bordo della CHASSERAL. La nave ora risultava fortemente sbandata verso il lato di dritta e nella sala macchine l’acqua era alta tre metri. Anche nella stiva numero 3 era entrata acqua. Il comandante e gli ufficiali credevano che la nave era ormai irrimediabilmente persa, tornando a bordo del pattugliatore alle 21.30 il quale alle 02.00 gli aveva portati in salvo a terra nel porto di Sété. Senza ordine del comandante, la sesta flottiglia di sicurezza della Marina Militare tedesca stazionata a Marsiglia tentava di recuperare la CHASSERAL. Diverse navi partecipavano al recupero, tra le quali anche il battello di scorta M-6031, il quale rimorchiava la CHASSERAL gravemente danneggiata in direzione Sété, e dopo quattro ore e quarantacinque minuti circa a rimorchio, la poteva arenare a nordest del porto. A quanto pare, durante questa operazione di salvataggio anche un idrovolante di salvataggio marino, Dornier DO24, era stato perso, affondando nelle vicinanze della CHASSERAL. Tuttavia nessuno dell’equipaggio aveva notato tale velivolo e la perdita era avvenuta sotto circostanze misteriose. L’intero recupero durava 11 ore e stava sotto il comando del capitano di corvetta Hermann Polenz.

Capitano di corvetta H. Polenz (a destra) in conversazione con uno di tanti ammiraglio di quei periodi

Hermann Polenz (2. da sinistra) in conversazione con i suoi ufficiali Fonti: da una pubblicazione commemorativa del raduno di camerati della 6. flottiglia di sicurezza, Marsiglia, eredità di Franz Hauser (Ruhr & Saar Kohle AG, Basel) / Albert Vogel Il defunto Maurice Jaccard era stato seppellito il 25-04-1944 nel cimitero di Sété in presenza del comandante e l’intero equipaggio. Era il primo ed ultimo marittimo svizzero deceduta tramite azione bellica durante il secondo conflitto (vedi sotto). Il carico era stato trasbordato sulla ZÜRICH per trasportarlo a Lisbona. Dopo una provvisoria riparazione a Sété, la nave poteva ripartire il 07-06-1944 e continuare il viaggio verso Lisbona, dove arriva il 12-06-1944. Nel cantiere Companhia Uniao Fabril erano poi state eseguite le necessarie riparazioni, le quali duravano fino al 31-07-1944 dopodiché la nave era stata rimessa in servizio. Nello stesso periodo circa, aerei inglesi avevano attaccato due navi della croce rossa nella stessa area, la EMBLA era stata affondata il 19-04-1944 e la CHRISTINA danneggiata il 06-05-1944. Questo attacco ovviamente procurava molta attenzione ai giuristi, le udienze si stendevano per parecchi anni fino ad arrivare ad una conclusione. Non vogliamo perdere tante parole in merito, le informazioni dell’archivio federale sono rapsodici e in parte contraddittorie. La Svizzera valutava il danno tra nave e carico sui 2,7 milioni di Franchi Svizzeri e reclamava risarcimento alla Gran Bretagna. Dopo dure trattative con la Svizzera, gli inglesi concordavano un risarcimento di 50'000 Sterline allora 867'000 Franchi, pagate tramite assegno nell’aprile del 1949. Alla vedova di Maurice Jaccard erano state versate unicamente un importo di 35'000 Franchi come risarcimento. La Marina Militare tedesca chiedeva un 20% del valore della nave e del carico per le operazioni di recupero, come anche 1,3 milioni di Franchi Svizzeri per l’idrovolante perso. Le autorità svizzere mettevano in discussione l’intervento del velivolo di salvataggio marittimo per una nave abbandonata e alla deriva, una risposta non l’abbiamo trovata ne a Berna ne in archivi tedeschi, è da presumere che importanti documenti siano stati smarriti durante il periodo bellico. Non siamo a conoscenza, se le trattative erano state concluse, tanto più che un anno più tardi il Reich era sparito nelle macerie.

Un Dornier DO24, idrovolante utilizzato come mezzo di salvataggio marittimo durante la seconda guerra mondiale, ma anche dopo il conflitto Le persone tedesche coinvolte nel salvataggio infine chiedevano come ricordo e regalo un orologio. Dopodiché le nostre autorità valutavano il regalo politicamente non problematico, autorizzavano l’assicurazione svizzera (era responsabile dell'assicurazione di guerra), di consegnare i regali. Se poi effettivamente erano stati dati ai marittimi non siamo riusciti a constatare. Persone decedute in servizio della Svizzera durante il secondo conflitto mondiale Durante la seconda guerra mondiale sono decedute alcune persone tramite atti bellici in servizio per la marina mercantile svizzera, incluse le navi a noleggio. Maurice Jaccard però era l’unico svizzero che perse la vita in tale modo. Altri svizzeri però sono morti par causa di incidenti di lavoro a bordo delle navi i quali però non avevano niente a che fare con le attività belliche. La più grande perdita con 30 morti riguarda la nave greca MOUNT LYCABETTUS noleggiata dal KTA e sparita senza lasciare tracce dopo la partenza da Baltimore nel marzo 1942. Appena dopo la guerra si era in grado di venire a conoscenza tramite documenti tedeschi e giornali di bordo, che al pomeriggio del 17-03-1942 era stata affondata tramite due siluri dal sommergibile tedesco U-373 (comandante Paul-Karl Loeser). Il 07 settembre 1943 aerei britannici affondavano la nave MALOJA nei pressi dell’isola di Corsica, provocando la morte di tre marittimi portoghesi, mentre il primo ufficiale, un olandese, e un cuoco svizzero riportavano gravi lesioni. Un anno più tardi, il 19 settembre 1944 nel porto di Marsiglia la nave GENEROSO era in procinto di cambiare ormeggio. Durante tale manovra, verso mezzogiorno, urta contro una mina a centro nave, mandandola a picco. In seguito questa esplosione il comandante russo Anatol Gouretzky ed il marconista svizzero Christian Schaaf venivano scaraventati in aria e fuoribordo. Mentre il comandante perse la vita, il marconista caduto in acqua con gli indumenti in fiamme era stato salvato con gravi lesioni. Annotazioni in merito attacco a navi neutrali Nella parte inglese della nostra storia abbiamo aggiunto alcune annotazioni dal libro “The Armed Rovers: Beauforts and Beaufighters over the Mediterranean”, di Roy Coneyrs Nesbit (Casemate Pubblishers, 2014) Non vorremo tradurre tali righe, ma notificare, che i piloti avevano ordine di attacare e affondare immediatamente ogni nave nell’area in questione. SwissShips HPS, HM, MB, Gennaio 2020 Fonti:

|

![]()

History

This cargo steamer was launched on 20.08.1897 at the Scottish shipyard Hall, Russell & Co. of Aberdeen (hull No.: 303). It was completed as INGELI and delivered in October 1897 to the owner company John T. Rennie, Son and Company, Aberdeen (official No.: 108651, call sign: PVJD). The ship was powered by a triple-expansion steam engine, also built by Hall, Russell & Co (1,810 HP), and reached a speed of 12 knots, a high speed at the time. It also offered space for 36 passengers. Originally, the ship was still equipped with yards on the foremast for auxiliary sails. The cargo gear consisted of 3 derricks. The word INGELI comes from the Zulu language and means cold, snow or sleet, but is also the name of a mountain in KwaZulu-Natal. In 1911 the steamer was sold to Charente Steamship Co. Ltd. of Liverpool and the management was allocated to Thos. & Jas. Harrison, also of Liverpool. 1913 she was purchased by the Honduran company Vaccaro Brothers Ltda. La Ceiba and registered under the flag of Honduras with the new name of TEGUCIGALPA (call sign: HRBB). In April 1920 the Tegucigalpa Steamship Corporation became the new owner, with the previous owner, Vaccaro Brothers Ltda. taking over its management. At the same time, the ship was converted from coal to oil firing. In 1924 the ownership changed to the Standard Fruit & Steamship Co. La Ceiba but with the management remaining with Vaccaro Bros. In 1933, the Standard Navigation Corp. La Ceiba acquired the ship and handed over the management to Standard Fruit & Steam Ships Co., New Orleans. In 1936 the passenger capacity was reduced to 12 and at the same time 5 more derricks were installed. The vessel was sold on 24.03.1941 to the Greek shipowner Nikolaos Konialidis, from Buenos Aires, a cousin and also brother-in-law of Aristoteles Onassis, who continued to operate the ship under the same name and flag. In March 1941 the steamer arrived in New York for repairs before it was chartered by North Atlantic & Gulf Steamship Co. The repairs were unplanned and the charterer was not very happy about these delays. Due to these circumstances the charter was cut by half and the ship made only one trip for N. A. & G. The owner tried to get rid of the ship as quick as possible and found a new buyer with the Swiss Confederation. On 03.07.1941 the Federal War Transport Office (KTA) bought the ship for the Confederation and took it over in New Orleans. The shipping agency Honegger & Ascott in London took over the management. With the entry into the Swiss shipping register on 17.07.1941 she received the name CHASSERAL and the call sign HBDF (survey data: GRT: 2,928, NRT: 2,702, DWT: 3,865). At the end of 1941 she was overhauled and partially rebuilt in Lisbon at the Companhia Uniao Fabril shipyard (new tonnage survey: GRT: 3,128, NRT: 1,874, DWT: 4,064). 60% of the steel parts of the ship were renewed at that time. The oil firing was again replaced by conventional coal firing, since coal was much easier to obtain during the war than marine or diesel oil. During 1941 the CHASSERAL brought grain from the U.S.A. to the Mediterranean ports and loaded Swiss export cargo for the States. In 1942/43 she was employed in the shuttle service from Lisbon to Genoa, Marseille and Toulon. The Greek vessels, chartered by the Swiss Government were not allowed anymore to enter the Mediterranean Sea and had to unload their cargo from overseas in the port of Lisbon. On 21.08.1943 the CHASSERAL was in the port of Lisbon where she took over a load of copra from Mozambique from the KTA-chartered Greek steamer MARPESSA. During the cargo transfer a fire broke out in holds 1 and 2 which could be extinguished by the ship's crew and the fire department. As the ship had threatened to capsize it was grounded outside the port of Lisbon in the Mar da Palha at Barreiro. However, this measure proved unnecessary and the ship was refloated. In 1944 the vessel was sent overseas again and made two voyages to Central America, loading mainly coffee, but also other produce. One trip went to Philadelphia to fetch a full cargo of grain. On a voyage from Marseille to Lisbon on 22.04.1944, the CHASSERAL was attacked by British fighters off the coast of Sété leaving one crew member dead and five injured. The steamer was towed into Sété and after some temporary repairs she sailed on to Lisbon where permanent repairs were effected (see report below). Throughout part of the critical war period, the CHASSERAL was commanded by Belgian Captain Marcel Henrotin, who was born in Sardinia in 1906 and lived in Switzerland. Captain Louis Jean Van Hoeberghen, also Belgian, also served as captain on the steamship CHASSERAL from 6 January 1942 to 18 October 1943, from 21 November 1943 to 6 February 1944 and from 6 July 1944 to 27 July 1944. In between, he also commanded the steamship EIGER. During the Second World War, he spent more than two years on the CHASSERAL and one month on the EIGER.

Captain Louis Jean Van Hoeberghen After the war the CHASSERAL continued to sail for the KTA, throughout 1945 she carried cargo from Lisbon to the ports in Italy and France for onward transportation to Switzerland, as huge stocks of goods had accumulated in Lisbon. The following year she was employed on voyages to Brazil, West Africa and the U.S.A. On 11.03.1947 the federal government sold the ship for 800,000.- Swiss francs to Nautilus AG, of Lugano and Glarus, Switzerland, with the flag, name and call sign being retained on the change of ownership (new tonnage: GRT: 3,129, NRT: 2,702, DWT: 4,064). The shipping company used the steamer mainly in the West African trade, but in 1948 until early 1949, the ship was engaged on a voyage to India, with various port calls, including Bombay and Karachi. Although the SMNO (Swiss Maritime Navigation Office) in Basel did not allow Nautilus to carry more than 12 passengers on board their freighters, this rule was breached on the CHASSERAL and gave rise to discussions and was considered a gross offence. In addition, a company from Zurich complained to the federal government about the lousy accommodation given on board to one of their passengers, which they considered as unworthy for a Swiss flag vessel. Nautilus AG sold the meanwhile 54-year-old steamer on 08.07.1951 to the ship owner Franco Maresca fu Mariano in Genoa. In a small ceremony in the port of Genoa the Swiss flag was lowered on 10.10.1951 at 11:30 in the presence of a consular officer and the ship handed over to the new owner. Present at the handover were Christian Bach, office chief in Genoa, the two inspectors Lisi and Spinella, and Captain Donato for Nautilus, and the new ship owner Franco Maresca, his inspector Moretti and the new Captain Lavarello for the buyer's side. Franco Maresca had the ship renamed as MAR CORRUSCO and put her into service under Italian flag. In 1953 the ship was sold for demolition to the company A.R.D.E.M. in Savona. Additional information and stories Under the command of Captain Marcel Henrotin the CHASSERAL left on Saturday morning 22.04.1944, the port of Marseille with destination Lisbon. Her cargo was only 361 tons, but consisted of high value Swiss export goods such as machine parts, watches and pharmaceutical products, worth about 9 to 11 million Swiss francs. At that time the south of France was still occupied by the German Wehrmacht and the entire sea area on the French Mediterranean coast was under the control of the German navy. But the coast was also within the reach of Allied forces, especially the aircrafts of the RAF, coming from Italy, Corsica or North Africa. While the CHASSERAL sailed west on the prescribed course south of the Rhone Delta, 8 to 10 fighters planes attacked the freighter at 17:10 in the late afternoon. They came from the direction of the coast and attacked the vessel's starboard side. The raid occurred at position 43° 22’ 30'' North / 004°05’ 00'' East, approximately 6 nautical miles south of Pointe Espiquettes and about 15 nautical miles east of Sète. The water depth at this point was about 53 meters. The weather was fine and there was a clear view. In addition, the war markings, i.e. the Swiss flags on the side and on deck, and the word "Switzerland" had been repainted in the port of Marseille and were clearly visible. The aircraft attacked the freighter in waves of three, from a low-altitude of about 80 to 100 metres with cannon and rockets. Afterwards they returned and flew a second attack, before they disappeared south over the open sea. The Swiss greaser Maurice Jaccard from St. Croix was badly injured and he died an hour later in the lifeboat. Five Portuguese seamen were also injured. The aircraft were identified as British Bristol Beaufighter fighter-bombers. These were part of the RAF 39th. Squadron flying from Alghero in Sardinia. The same squadron was also responsible for the attacks on the MALOJA and the CHRISTINA and still operates today (2020) flying Predator drones.

Source: The Aviation History Online Museum British friends even suspected that the watches in the cargo were in reality time fuses for bombs and similar ammunition and the air raid was carried out for this reason. Well, if these fuses were destined for the Germans, they could have been shipped directly to Germany by road or rail, it was therefore an absurd idea. On the other hand, the British searched our ships each time they passed Gibraltar and both war parties received information about the voyages of our vessels. It must be assumed that the squadron leader acted without authority or made a misjudgment. On the voyage to Lisbon the crew was interrogated by the Royal Navy about the incident. In any case, the United Kingdom did not deny its responsibility for the attack. The ship suffered a lot of shell damage on the starboard side, the bridge and officers’ quarters were also badly damaged. The starboard lifeboat was destroyed and unusable. However, it seems that all holds made only little water and remained mainly dry, but according to a damage list, the cargo also suffered some serious damage. Probably the biggest damage was caused by an "8cm rocket bomb", according to the description of the Kriegsmarine, which penetrated into the engine room through the side and exploded in the steam condenser of the main engine, whereupon the engine room was flooded to above the cylinders. This explosion hurled the greaser Maurice Jaccard with brutal force against the column of the medium pressure cylinder, inflicting serious head and leg injuries. After the engine was stopped and the fires in the boilers were extinguished, the master ordered the starboard anchor to be dropped. Then the crew and the captain left the ship in the intact port side lifeboat, so as not to provoke further attacks. After two hours the harbour patrol boat FSE-04 of the German Navy took the crew on board and brought them back to the CHASSERAL. The ship now had a heavy starboard list and in the engine room the water was 3 metres deep. Also hold 3 made some water. The captain and his officers believed that the ship was irretrievably lost and at 21:30 they boarded the patrol boat and were taken to safety at Sète, where they arrived at 02:00 in the morning. Without being commissioned by the master, the Marseille-based 6. Sicherungsflotille (6th security flotilla) of the German Navy tried to salvage the CHASSERAL. Several ships participated in this salvage, among others the escort vessel M-6031. They managed to tow the heavily damaged ship towards Sète and after about 4¾ hours of towing, the CHASSERAL was put aground northeast of the port of Sète. During this salvage operation, a new German rescue seaplane, a Dornier DO24 (worth 1.3 million francs) was apparently also lost, sinking to the bottom close to the CHASSERAL. However no one of the crew has seen this seaplane and its loss occurred under very mysterious circumstances. The whole salvage operation lasted 11 hours and stood under the command of Lieutenant Commander Hermann Polenz.

Lieutenant Commander H. Polenz (right)with one of the many admirals of that time

Hermann Polenz (2nd. from left) talking to his officers The deceased Swiss greaser Maurice Jaccard was buried on 25.04.1944 in the cemetery of Sète in the presence of the captain and the entire crew. He was the first and only Swiss seaman to die in World War II by military action (see below report). The cargo was transferred to the ZURICH for onward transportation to Lisbon. After some temporary repairs were carried out in Sète, the CHASSERAL was able to leave the port on 07.06.1944 and continued her voyage to Lisbon, where she arrived on 12.06.1944. After permanent repairs at the shipyard Companhia Uniao Fabril, which lasted until 31.07.1944, the CHASSERAL was able to resume her normal service. At about the same time, British planes attacked two Red Cross ships in the same sea area, one was the Swedish-flagged EMBLA, which sank on 19.04.1944 and the other was the Spanish-flagged CHRISTINA, which was damaged on 06.05.1944. Of course, this raid resulted in a series of legal proceedings, which took several years to complete. We do not want to lose a lot of words about this issue, our information from the federal archive is incomplete and partly contradictory. Switzerland estimated the damage to ship and cargo at 2.7 Mio. Swiss francs and demanded compensation from Great Britain. The British agreed after tough negotiations to pay 50’000.- Pounds Sterling, which was paid with a check, at the time worth 867,000.- Swiss francs. The widow of Maurice Jaccard received a one-off payment of 35,000.- francs as compensation. The German Navy demanded a salvage award of 25% of the value of the ship and its cargo, as well as 1.3 Mio Swiss francs as compensation for the lost seaplane. The Swiss authorities questioned the use of a seaplane for the salvage of a drifting and abandoned ship, but we have not been able to find an answer in either the Swiss or the German archives. One can only assume that many important documents were lost in the confusion at the end of the war. We don’t know if the negotiations with Germany were actually concluded, especially as the “German Reich” ended in ruins a year later.

A German rescue seaplane Dornier DO24, as used during World War II, but Eventually, the German sailors involved in the salvage wanted to receive a Swiss watch as a souvenir and a gift. After our authorities had classified this gift as being politically without problems, they authorized the Swiss Reinsurance company, which handled war insurance, to go ahead. Whether the sailors actually received their watches could not be determined. Deceased seamen in the service of Switzerland during World War II During the World War II a few seamen in the merchant service of Switzerland suffered death from attacks of the two war parties, including those on chartered vessels. However Maurice Jaccard was the only Swiss citizen who lost his life in this way. Other Swiss died of accidents on board, which had nothing to do with the war events. The greatest loss with 30 men perished, occurred when the MOUNT LYCABETTUS disappeared without trace in March 1942. This Greek vessel was chartered by the KTA, Bern and only a few days after departure from Baltimore ceased sending any position messages. It was only after the end of the war that it was discovered from German documents and log books, that the German U-373 (commander Paul-Karl Loeser) had sank the vessel with two torpedoes in the afternoon of 17.03.1942.On 07.09.1943 British fighter planes attacked and sunk the freighter MALOJA off the coast of Corsica. Three Portuguese Seamen lost their life and the Dutch 1st officer a Swiss cook were badly wounded. Again one year later, on 19.09.1944 the steamer GENEROSO had to shift in the port of Marseille. During this manoeuvre she was hit by a drifting mine on her midship. The severe explosion hurled the Belarussian captain Anatol Gouretzky and the Swiss radio operator Christian Schaaf high into the air and overboard. The captain lost his life, while the sparky fell with burning clothes into the water and was rescued with serious injuries. Some comments on attacks on neutral ships Attack on the CHASSERAL, 22.04.1944 Attack on the Red Cross ship EMBLA, 19.04.1944 Attack on the Red Cross ship CHRISTINA, 06.05.1944 SwissShips: HPS, MB, NB, February 2020

Sources:

|

![]()

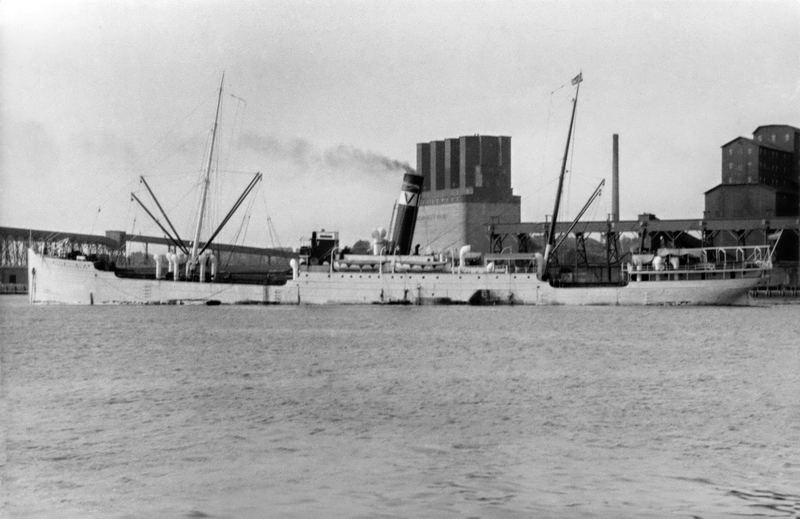

Auf dem Tejo vor Lissabon / On the River Tagus off Lisbon

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © Seeschiffahrtsamt Basel |

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © Johnny Hungerbühler †

|

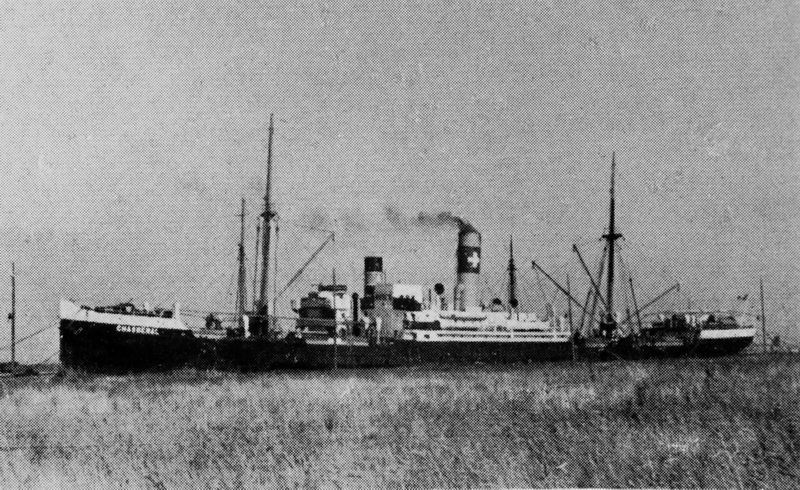

Auf dem Tejo vor Lissabon / On the River Tagus off Lisbon

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © Unbekannt / Unknown / © SwissShips / Archiv |

In Lissabon während dem 2 Weltkrieg in den KTA Farben / At Lisbon during WW II in KTA = war transport office colours

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © Unbekannt / Unknown / © SwissShips / Archiv

|

In Lissabon während dem 2 Weltkrieg in den KTA Farben / At Lisbon during WW II in KTA = war transport office colours

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © Sammlung Jean Louis van Hoeberghen

|

.jpg) In Toulon am 23. März 1944 während der 1. Reise in diesen Hafen / In Toulon on 23 March 1944 during the first voyage to this port

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © Sammlung Harald Ihringer / Der Fotograf ist möglicherweise der Journalist Marcel Bolomey?

|

In Marseille nach dem Krieg in den KTA Farben / At Marseille after WW II in KTA = war transport office colours

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © Funker L. Leibundgut

|

In Marseille nach dem Krieg in den KTA Farben / At Marseille after WW II in KTA = war transport office colours

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © Marius Bar

|

Nach dem Krieg in den KTA Farben / After WW II in KTA = war transport office colours

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © Unbekannt / Unknown / © SwissShips / Archiv

|

In Lissabon mit Nautilus Farben / At Lisbon in Nautilus clours

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © Capt. J. F. van Puyvelde †

|

In Marseille in den Nautilus AG, Glarus & Lugano Farben / At Marseile in Nautilus SA colours

|

In Marseille in den Nautilus AG, Glarus & Lugano Farben / At Marseile in Nautilus SA colours

|

Wir suchen Fotos / Photographs wanted

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © SwissShips / FotoMar

|

|

Berichte über die angegriffene CHASSERAL

S/S CHASSERAL im Swiss Observer 19464

|

|

vorher als / previously as

In St. John, N.B. am 16. August 1929 / At St. John, N.B. August 16, 1929

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © By the late John Lochhead via Bill Schell

|

Wir suchen Fotos / Photographs wanted

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © SwissShips / © FotoMar

|

|

später als / later as

Aufgenommen auf dem Tejo vor Lissabon 1953 / Photographed 1953 on the River Tagus off Lisbon

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © Capt. J. F. van Puyvelde †

|

Wir suchen Fotos / Photographs wanted

Bildherkunft / Photosource: © SwissShips / © FotoMar

|